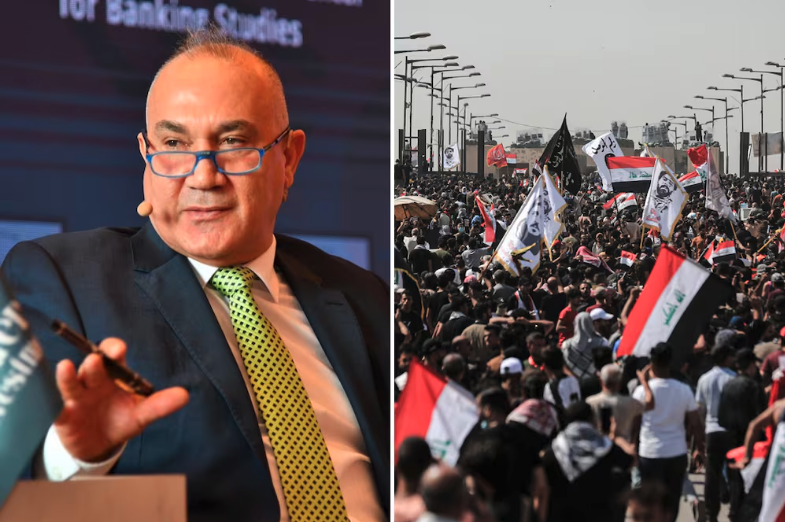

A failing post-conflict economy hit by corruption woes prompted Mohammed Ihsan to search for new solutions in academia

A failing post-conflict economy hit by corruption woes prompted Mohammed Ihsan to search for new solutions in academia

Throughout the years Mohammed Ihsan spent driving across Iraq’s dusty roads in search of mass graves that were the hallmark of Saddam Hussein’s legacy in Kurdistan, a keen sense of hope was the driving force of his mission.

Hope of a breakthrough that would offer families closure following decades of grieving for their missing sons, fathers and husbands; hope of justice for the slain victims whose bodies lay mangled in pits; hope of holding the perpetrators to account.

As Iraqis mark the 20th anniversary of the invasion of their homeland that sense of a hopeful future appears to have faded from Prof Ihsan as he looks at a country embroiled in economic turmoil. His professional focus has turned from the historical quest for justice for victims to the Iraqi economy. Its trajectory since the conflict is one of missed opportunities and endemic corruption.

The result has been a plunging Iraqi dinar, persistently high unemployment and widespread poverty. The aspirations held by people in the days after Saddam’s regime are a distant memory٫

Prof Ihsan spent 17 years serving in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and Iraq’s federal government before taking up an academic career. He told The National the dismal state of the country spurred his efforts to research new solutions for economic reform.

Prof Ihsan, who works as a visiting senior research fellow at Kings College London, now rules out a return to Iraqi’s complex world of politics. But given his lifelong quest to uncover truth where it lies buried, the former mass grave hunter does not shy away from offering his opinion on the issues blighting Iraq.

Hope has dimmed

“I think it’s a hopeless case,” he said. “We have a problem of people — the elite — coming into power and they are not ready. They are politics lovers, not politicians.

“When Iraq moved from an authoritarian system to democracy it was totally different. With the money the economy has gained since 2003 we could have built three new top-class Iraqs since then with that money. We could have the best education, the best infrastructure. But nothing has been done.

“The majority of the people are poor and are upset by what’s going on.”

US Fed acts on Iraqi corruption

Since the US-led coalition invaded Iraq in March and pushed out Saddam’s brutal regime in 2003, the US has controlled the flow of dollars to Iraq as the troubled nation’s foreign reserves have been held in the Federal Reserve.

The US Federal Reserve in February restricted Iraq’s access to its dollars in a bid to counter money laundering. The decision stemmed from fears in Washington that such misconduct is benefiting Iran and leading to the funding of terror groups.

The move underscored the endemic corruption that Iraq has struggled to shake off in the post-Saddam era. Unease about the country’s struggle to break free of dishonest conduct by those at the top is a sentiment held across society and has even penetrated the government in Baghdad.

Iraq scored towards the lower end of the scale — 23 points out of 100 — in Transparency International’s 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index.

To stabilise Iraq’s political environment, Prof Ihsan has suggested a reformed political system in which each of Iraq’s different ethnic and religious groups would have their own representatives.

“Every group is thinking about their own interests,” he said. “Iraq is one of the countries where there is a complexity of national identities. Each group translates the constitution according to their own interests. People are not united. Even if they have nothing to fight about they fight among themselves.”

To conquer the beast of corruption Iraq needs international help, analysts say, in the same manner it required the help of outsiders to rid its land of ISIS.

Prof Ihsan backs this position, and suggested the US should serve as a supervisor of a new era of cleanhanded dealings in Baghdad.

He warns that the economic situation in the country has arrived at a “critical” point, with Iran’s influence in the country’s political system creating a “rotten apple” culture.

“No one can run a show like this,” Prof Ihsan said.

Rather than pointing fingers at foreign powers who have in the past interfered in the nation’s affairs, the time has come for Iraqis “to get their own initiative and for the US to supervise this”, he said.

Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia Al Sudani called the US Iraq’s “strategic partner” this week in a sign of his new government’s thinking on relations with Washington. Prof Ihsan has been encouraged by the new leader’s apparent willingness to work for the good of all Iraqis, including minorities, and called him a “good guy”. But he stressed that to create any change he needs the support of those around him.

The lecturer, who has published 14 books mainly on Iraqi politics, resides in Erbil. The standard of life in the semi-autonomous Kurdish region pales in comparison to the experience of Iraqis in other areas, he said.

“It’s totally different in Kurdistan,” he said. “Still, we have a lot of economic issues. ISIS still exists [and] Iran is still bombing.” He was referring to Iranian drones and rockets hitting the headquarters of Iranian Kurdish parties in the KRG last November.

Mass graves

Many moons have passed since Prof Ihsan began his intricate work of searching for mass graves.

His grim mission was the subject of a well received Channel 4 documentary in 2006, Iraq: Saddam’s Road to Hell. It explored how the former minister for human rights in the KRG worked to find the remains of about 8,000 men and boys from the Barzani clan who had disappeared from Kurdistan in the early 1980s.

At the end of the Iran-Iraq war, Saddam’s ruling Baathist party carried out what human rights campaigners say was genocide. Targeted at rural Kurds, the aim of the operation was to eliminate rebel groups who were fighting against his government and had sided with Tehran.

“I found a huge amount of evidence and stories which cannot be told,” he said. “I found documents in Saddam’s homes and archives.

“I found three mass graves of the Barzanis,” he said, with the sight of bodies serving as a stark legacy of “the cruelty of the [Saddam] regime”.

“Dealing with bodies and graves is not easy and it had an effect on me psychologically.”

He is not alone. In Baghdad efforts to document the mass graves are continuing. Officials say 260 mass graves have been unearthed in the last two decades, with dozens still closed because of limited resources.

A team made up of about 100 people in a section of the ministry of health continues to process remains from mass graves, one site at a time.

The unit has identified and matched DNA samples of about 2,000 people, from about 4,500 exhumed bodies.

Separately, archivists identify about 200 new victims each week by studying stacks of documents from Saddam’s Baath party, which was disbanded after his removal.

Decades on, the lecturer believes much of Iraq’s society remains traumatised from such dark days.

Prof Ihsan said many who were politicians during the 80s, 90s and after the turn of the century “accept their failures,” but the road for citizens to forgive their leaders is a difficult one and younger Iraqis will only enjoy a more prosperous future than their forefathers if they are committed to doing the work required.

“In Iraq it’s very easy for a victim to become a perpetrator. It’s also easy for a perpetrator to become a victim,” he said.

“From my work, I found out that the cheapest thing in Iraq is human life.”